Who Owns the Coastline?

Mary T. McCarthy

As we hunt the coast in search of ocean treasure, we can occasionally find ourselves as beachcombers crossing into unknown territory when it comes to who owns the beach. Often it’s clear. When we are on a state or national seashore resort park or other clearly marked coast where visitors are welcome, we pack up our beachcomber-to-go bag, and we are ready for the hunt (or, as some people may refer to it, a “walk on the beach”). But other times, when an obvious house is not present, and even when it is, ownership of the place where the tide meets the shore can be in question.

Signs, signs, there are often everywherethe signs. No trespassing. Stay Off Beach. Private Property. Beach Access Not Permitted. And on and on. Sometimes the issue isn’t the ownership of the coastline as much as the ownership of the access to the coast. Property owners often control the land that leads to the beach. But what if you arrive in a boat, or by walking along the coastline from an adjoining property, simply by strolling down the beach? Well, the waters can get pretty murky.

In reality, courts have ruled in many cases that no one owns the actual coastline. This is roughly how it works: Federal coastal laws vary in different parts of the country, since each state has different laws. Under what’s known as “riparian” law, according to Wikipedia, “water is a public good like the air, sunlight, or wildlife. It is not ‘owned’ by the government, state or private individual but is rather included as part of the land over which it falls from the sky or then travels along the surface.”

Of course, we don’t always beachcomb in the water (except at trash dump beach sites, where we do, because that’s usually where the marbles are). The interesting part of the definition about riparian rights as it affects beachcombers, though, is that the coastline falls within the definition of the term. Wiki adds: “The land below navigable waters is the property of state, subject to all the public land laws and in most states public trust rights. Navigable waters are treated as public highways with any exclusive riparian right ending at the ordinary high water mark.”

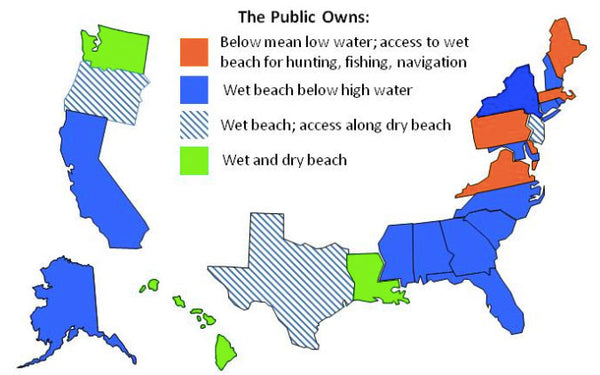

Basically the beach is like the side of the state highway, up to the high tide line, and no one “owns” it since it’s covered in water twice a day. That’s the law in most east coast states (except Maine, Massachusetts, Delaware and Virginia, where it’s low tide line). The states with the best and most public-use friendly coasts are Oregon and Texas.Beachapedia.org is a great website for getting more information about what is and isn’t legal on different coastal areas around the country. They report that “Of all the U.S. coastal states, the state of Oregon may have the best legal protection for the public’s use of and access to its coastal land. Thanks to Oregon’s landmark ‘Beach Bill’ passed in 1967, the public’s right to access to all of the state's beaches is guaranteed. Additionally, the Bill establishes a state easement on all beaches between the low water mark and the vegetation line.”

Oregon implemented a Coastal Zone Management program stating that the beach is a public right of way and the public has the right to free, unrestricted access along the entire Oregon coast, making Oregon the national leader in public beach access programs.

The 2009 documentary “Politics of Sand” details how the Beach Bill applied customary use doctrine and created law stating that if the public's recreational use of an area “has been ancient, reasonable, without interruption, and free from dispute, such use, as a matter of custom, should not be interfered with.” Hawaii also secures public land all the way to the line of vegetation, and Texas has a statewide law guaranteeing the public the right to unrestricted access to its coasts.

Regardless of state laws, for beachcombers trouble can occur when private beachfront property owners don’t know and/or don’t care what the laws are. Razor wire fences, bulkhead and giant riprap walls are often erected (sometimes illegally or without permits in critical area watersheds) to keep beachcombers away.

Small craft boaters, kayakers, surfers and other recreational watersport individuals are often faced with the issue of whether or not to land themselves and their vessel on a stretch of beach. Common sense should always be the guide here. Choosing not to land on a property with 10 feet of sandy beach, two Adirondack chairs, and a tiny cottage 20 feet from the shore is just polite. No beachcomber should want to trespass on what appears to clearly be personal property, but crossing a property at a shoreline is another matter. A vast sandy shoreline, no buildings in sight, hundreds of acres of open land at low tide? Seems like it should be accessible to a beachcomber. Nobody owns that coastline, and what washes up there is essentially finder’s keepers.

Several parks on coasts at each end of the country, one a state park and one national, beg to differ. Once a landfill, Fort Bragg, or Glass Beach, in California, is a famous sea glass destination, though it’s embroiled in controversy. At MacKerricher State Park it is illegal to remove glass from the beach. The park wants the broken glass to remain there for “future generations to enjoy.”

At the opposite coast, Dead Horse Bay in New York City, a landfill trash dump of epic proportions with thousands of broken bottles strewn everywhere and continuing to erode, is also (as it’s referred to in the ABC documentary “Dead Horse Bay”) “Federally protected trash.” These aren’t smoothly polished nuggets of glass that are beautiful to behold like in California, either. It’s an actual trash dump beach, clearly hazardous to marine life, but of interest to beachcombers because of the marbles, perfume stoppers, porcelain figural pieces and other treasures that can be found amongst the broken glass pieces. There is no “sea glass” at Dead Horse Bay.

Rangers will approach beachcombers at both Fort Bragg in California and Dead Horse Bay in New York and have you return your finds (Spectacle Island in Boston is another Federal State Park where sea glass is forbidden from being taken).

Beachcombers need to practice personal ethics when it comes to whether or not to keep finds from these places. Some would argue that even the government doesn’t own the coastline. At onthecommons.org it is noted that coastal access court cases against the government at the state level have been lost due to the “public trust” doctrine, which goes back to Roman times. Public trust declares that waterways are inherently public, and cannot be sold even if the sovereign decrees it. The first U.S. court to articulate the public trust was the New Jersey Supreme Court, in a 19thcentury case involving oyster beds. “[W]here the tide ebbs and flows, the ports, the bays, the coasts of the sea, including both the water and the land under the water…are common to all the people.”

More beachcombing tips and gear recommendations

Recommendations for selecting the best beachcombing gear and more for your next trip to the beach. Articles ›

This article appeared in the Glassing Magazine September 2017 issue.

1 comment

I seem to remember reading somewhere that, while the coastline may be owned privately or by a state, the little rocks/islands that are not connected to shore and are visible at low tide all belong to the Federal gov’t…. Is that true?