Mudlarking: Coins, tokens, and forgeries

By Jason Sandy

Coin collection from the Thames (Jason Sandy).

While I was mudlarking one morning in April 2018, I spotted a stunning 17th-century trader’s token along the water’s edge. I wanted to photograph it in situ so I could post the token on Instagram. As I pulled out my smartphone to take a photo, a Thames Clipper boat roared past me, creating a large wave. I was so focused on taking the photo that I didn’t realize the wave was headed my way. With my back to the river, I snapped one photo before the wall of water unexpectedly hit me from behind, knocking me over. I was stunned and shocked as the water quickly retreated, sweeping my trader’s token into the river. I scrambled to find it, but the tide was coming in too quickly.

I was absolutely devastated! Determined to find the lost token, I decided to return to the spot at the next low tide around 11 pm even though I had to go to work the next morning. I tucked my kids into bed and read them a bedtime story before kissing my wife goodbye and leaving the house. I had to travel almost an hour from home to continue my search.

When I arrived back on the deserted foreshore, it was pitch black and eerily quiet. I was alone and unnerved. Strange sounds in the darkness startled me. I just wanted to find the token and return home as soon as possible. Unfortunately, I had forgotten to charge my headlamp because I hadn’t planned to go nightlarking. So, I was crawling on my hands and knees searching the exposed riverbed with the dim light from my smartphone. The situation seemed hopeless as I carefully combed the area where I had lost the coin. As I turned over a rock, I couldn’t believe my eyes.

Left to right: Gold coin found while nightlarking (Jason Sandy). King George III gold 1/3 guinea dated 1803 (Jason Sandy).

I struck gold! After six years of mudlarking, I finally found my first gold coin (above left). I was shaking with excitement as I held the precious coin in my hand. It’s a gold 1/3 Guinea coin from the reign of King George III (above right) dated 1803. I still can’t believe it. Fortunately, I was in the right place at the right time. I would not have gone mudlarking that night if I had not lost the trader’s token hours earlier. It’s a real story of serendipity.

Diocletian gold aureus coin (Tim Miller).

Although gold coins are extremely rare, some veteran mudlarks have found several of them in the Thames. In 2001, Tim Miller discovered a Roman gold coin (above) in mint condition. It is an aureus coin with the bust of Roman emperor Diocletian, who reigned from AD 284–305. On the back of the coin, Jupiter is depicted holding a thunderbolt in one hand and a scepter in the other. In the 3rd century AD, this coin was worth 25 silver denarii. Whoever dropped this coin in the Thames must have been absolutely horrified to have lost such a valuable coin.

King Francis I gold medieval coin (Tim Miller).

Several years ago, Tim found a stunning 16th-century gold hammered coin (above) from the time of the French king, Francis I, who reigned from 1515 until his death in 1547. This extraordinary coin is made of 24 carat gold and is called a “Ecu d’or au soleil du Dauphiné.” On the front of the coin, dolphins and groups of fleur-de-lis are shown within a circle subdivided into quadrants (the arms of the Dauphiné) beneath a radiant sun. On the back, a cross is formed with a quatrefoil in the center and fleur-de-lis at the ends. The Latin inscription declares: “Christ conquers, Christ reigns, Christ commands.”

King James I gold crown coin (Tim Miller).

Tim also found a gold “crown” coin (above) from the reign of King James I dating to 1615–1616. James is shown wearing a crown on the front of the coin that was minted at the Tower of London. The British royal coat of arms is illustrated on the back, along with the Latin inscription which proclaims: “Henry united the roses, but James unites the kingdoms.” This refers to Henry Tudor, who united the House of Lancaster (red rose) with the House of York (white rose) at the end of the Wars of the Roses in 15th century. Born in Scotland and raised by his mother Mary, Queen of Scots, James united the kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland when he became king in 1603 after the death of Queen Elizabeth I.

Because gold coins were so valuable, their weight was checked to ensure they had not been clipped or were underweight. The coins were literally “worth their weight in gold.” To verify that gold coins were not below their legal weight limit, square pieces of brass were produced in the 16th century to weigh the same as the gold coin equivalent. On a small scale, the gold coin was weighed in comparison to the brass coin weight.

16th-century coin weight (Portable Antiquities Scheme/PAS).

16th-century coin weight (Portable Antiquities Scheme/PAS).

A few years ago, Simon Bourne discovered a square coin weight (above) dated 1576, which depicts a horse and rider who is holding a sword above his head, charging into battle. A cross and four pellets appear on his breastplate. On the back of the coin weight, an upright hand symbolizing the city of Antwerp is illustrated with the numbers and letters “7 K” and “6 I” on either side of the hand. “K I” are the initials of the maker, and the six-pointed star under the hand indicates that he was appointed by the king. This coin weight was used in the 16th century to weigh a “Gouden Rijder” (Golden Rider) coin from the Low Countries.

King Henry VIII coin weight (John Mills).]

Special wooden cases were made to carry coin weights along with small scales. Over a period of a few months, John Mills unearthed several brass coin weights in a small area of the exposed riverbed. Perhaps someone dropped their coin weight case in the Thames. The wood disintegrated over time, leaving a cluster of coin weights on the riverbed. Most of the weights were made in either Britain or Antwerp. One of the finest examples John found (above) shows King Henry VIII seated on a throne and holding an orb and scepter. On the back of the coin weight, a crown is depicted above the letters “XX / S.” It was used to measure the weight of a gold sovereign coin from Henry VIII that was worth 20 shillings.

King Cunobelin gold quarter stater (PAS).

Over the years, mudlarks have found a wide variety of fascinating coins ranging from Celtic to modern times. Although several Potin coins from the Iron Age have been recovered from the river, only a few gold staters have been discovered in the Thames. Oliver Muranyi-Clark unearthed a rare gold quarter stater (above) from King Cunobelin of the Catuvellauni tribe. Between the letters CA and MV, an ear of wheat is depicted on the front of the coin. A rearing horse, long leaf, and the letters CVN appear on the back.

Caecilia Metellus silver denarius (Nicole Lanoue).

One of the oldest Roman coins from the River Thames (above) was discovered by Nicole Lanoue. It is a silver denarius from Caecilia Metellus dating to 130 BC. On the front, the helmeted head of Roma is facing right with a star beneath her chin. Jupiter is shown holding a branch and thunderbolt while driving a quadriga (chariot pulled by four horses) on the back of this ancient coin. The word “ROMA” appears in the exergue.

Counterfeit nummus of Diocletian (Jon Attenborough).

During the past ten years, I have found many Roman coins in the Thames. On Father’s Day in 2014, my kids took me mudlarking as a special treat. To my surprise, I discovered a large Roman coin (above) lying on the surface of the exposed riverbed. Produced in the 3rd century AD, the bust of Emperor Diocletian is depicted on the front, and a “genius” (a guardian angel in Roman religion) with a cornucopia in the left hand and patera in the right hand appears on the back of the coin. Although it looks like an officially minted coin, it is a contemporary copy of a bronze nummus coin. Counterfeiting and forging coins were rife in Roman times.

Roman forger’s coin mold (Jason Sandy).

One of the most interesting artifacts I ever found in the river is a forger’s mold (above) for making counterfeit Roman coins. The clay mold was used to produce Severus Alexander denarii coins when he reigned between AD 222–235. It is a double-sided, disc-shaped mold which was produced by pressing both sides of an authentic coin into a wet clay disc, leaving a concave imprint on the front and back. After creating several of these impressions in separate round discs and air drying them, the discs were stacked, and molten metal was poured into the concave voids between the molds. Once cooled, the molds were broken apart to retrieve the freshly, copied coins. I can imagine that a forger tossed this mold into the Thames to destroy the evidence and escape prosecution for counterfeiting coins.

By the 5th century AD, London had been abandoned by the Romans, and the Anglo-Saxons began arriving in the 7th century. They established a small village called Lundenwic, which became one of the greatest international trading centers of the Anglo-Saxons in Europe.

Saxon silver penny from Aethelred II (John Mills).

To facilitate commerce, Anglo-Saxons began producing silver pennies in the 8th century by hammering a blank disc of silver between two dies to impress a design into the coin. While mudlarking one afternoon in 2012 with her husband John and friends, Stephanie Mills discovered a Saxon penny (above) in extraordinary condition. John describes their experience: “I saw her look at something in her hand. In a flash, she stood upright and started walking hurriedly towards us. A certain smile on her face told me she had found something nice. I was stunned with what I saw as she placed a small silver disc in the palm of my hand. When flipping it over, I found myself staring at a beautiful, diademed bust. I turned the air blue with jubilation at the realization we had found our first Saxon penny!” Produced around AD 1009–1017, it is a small cross penny of Aethelred II and is the first coin ever to be recorded in the UK from the moneyer Osgar in Bedford.

King Eadberht silver sceat (Mark Vasco Iglesias).

Anglo-Saxons also developed silver coinage called “sceattas.” Often decorated with abstract animals and shapes, these small coins were beautiful works of art. Although sceattas are very rare, some mudlarks have found wonderful examples in the Thames. In 2021, Mark Vasco Iglesias picked up a Saxon sceat (above) from King Eadberht of Northumbria. Produced in the 8th century, the king is depicted facing right towards a long cross pommeé. On the back of the coin, there is a figure standing in a crescent boat wearing a cynehelm and pelleted robe, holding a long cross pommée in his right hand and a bird of prey in his left hand.

Left to right: Saxon sceat with abstract dove (Kevin James Dyer). 7th-century silver drachm from Iran (PAS). 15th-century silver groat of Henry VI (PAS).

In 2019, Kevin James Dyer found a stunning Saxon silver sceat (above left) dating to AD 680–710. On the front, a diademed head is facing right within a pelleted, circular border. An abstract dove is shown above a cross with two annulets on either side.

A few years ago, Tobias Neto found a very unusual Iranian coin (above center) in the River Thames. Dating to AD 590–628, it is a silver drachm of Khosrow II, the Sasanian king in Iran. The crowned bust of Khosrow II is surrounded by Zoroastrian astrological symbols, stars, and crescents around perimeter of the coin. Within a series of concentric circles, a holy fire-altar is flanked by two attendants on the back of the coin. It is possible that Anglo-Saxons or Vikings brought this coin to London before it was lost in the river. They had a vast network of trade routes around Europe extending to the Middle East.

Over the past forty years, mudlarks have found hundreds of medieval silver hammered coins, including shillings, groats (above right), sixpence, pennies, half pennies, and farthings. Many of the coins were produced in the Royal Mint, which was located in the Tower of London castle along the River Thames. Several silver hammered coins have been recovered from the river in mint condition.

15th-century penny forgeries (PAS).

Because the silver coins were very valuable, they were sometimes forged illegally. During the weekend of February 9–10, 1980, three mudlarks discovered the largest hoard ever found in the River Thames. Ian Smith, Roger Smith, and Paul Woods recovered 495 medieval pennies (above) from a small area of the Thames foreshore. No evidence of a container was found. As the coins were recorded and studied by the British Museum, it was established that they were all forgeries struck from false dies. They look like clipped coins because the forgers used silver discs which were too small for the larger size of the dies. The forgeries were made to imitate silver pennies of Edward IV from 1465–1483. However, they were likely struck in York around 1490–1500. The coins were made mostly of silver mixed with some copper. In the 15th century, the punishment for forgery was death, but the forgers still took the risk because of the huge profits they could make. Since the coins were found together on the riverbed, it is highly likely that the forger discarded them in the river to avoid being caught with the incriminating evidence.

In the medieval period, there was a lack of small denomination coinage. To make small change, silver pennies were sometimes cut into halves and quarters. Even these cut silver coins were often too valuable to make small purchases. Therefore, local communities created an unofficial currency using simple, decorated lead discs. These tokens were circulated in Britain from approximately the late 13th century to the mid-19th century.

Collection of lead tokens (Jason Sandy).

The earliest tokens were small, thin discs of pewter decorated with very fine motifs of ecclesiastical origin. Over the centuries, lead tokens became more popular and increasingly larger in diameter and thickness. In comparison with medieval pewter tokens, the lead tokens from the 17th and 18th centuries were very crude and appear to have been hastily produced. Lead tokens (above) were decorated with repetitive motifs such as a flower of six petals, cartwheels, fleur-de-lis, and anchors.

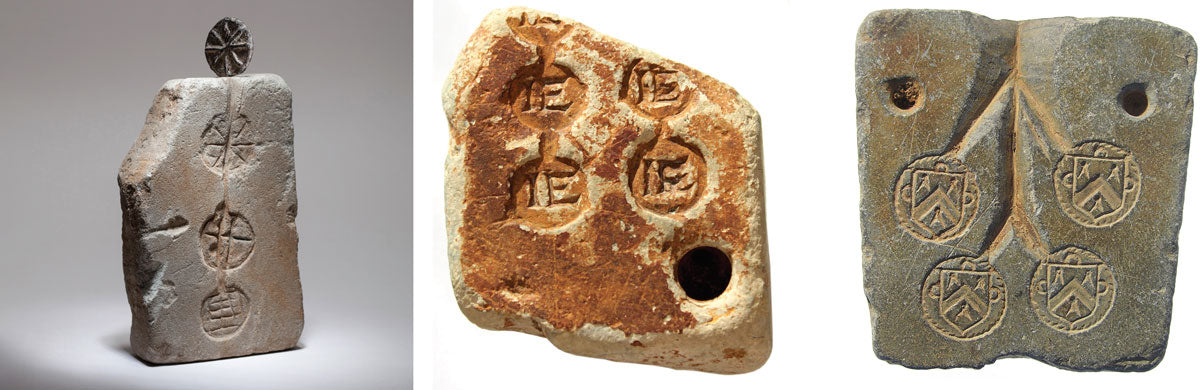

Left to right: Stone mold for three lead tokens (Hannah Smiles). Lead token mold carved in stone (Jason Sandy). Mold for producing tokens for the Worshipful Company of Carpenters (PAS).

Not only have mudlarks found hundreds of lead tokens over the years, they have also discovered the stone molds which were used to make the tokens. In 2015, I spotted a rectangular stone (above left), which had been carved to produce tokens with three different designs. The tokens are decorated with a 4x3 grid, two parallel lines intersected by a perpendicular line, and a crude star. A central, V-shaped groove was used as a casting channel to connect the three circular shapes. Molten lead was poured into the channel to create the single-sided lead seals. After the lead cooled, the tokens could be removed from the mold.

Mark Paros discovered a lead token mold (above center) made of stone which was used to produce six tokens of the same design. The initials “I E” of the token maker or business owner have been carved into each circular recess. The round shapes are connected by a shallow channel to allow the molten lead to run from one disc to the other. The person who made this mold forgot one thing—the initials should have been carved in reverse so that the letters would have been legible when the tokens were removed from the mold. Perhaps this mold was discarded in the Thames once the maker discovered they had made this fundamental error.

One of the best molds ever recovered from the Thames (right) is carved with four identical tokens. Within a circular recess, a shield has been carved with a central chevron and sets of dividers. This is the coat of arms of the Worshipful Company of Carpenters, which received its royal charter in 1477. From the top of the mold, a central funnel connects to the four discs. Two holes on either side of the mold would have been used to fix a flat stone against the mold with pegs. Lead was melted and poured into the gap between the two molds to create the simple lead tokens. This mold is possibly from the 17th century.

Unfortunately, no official records survive which document who produced the lead tokens, what they were worth, or where they were circulated. Based on the hundreds of lead tokens found each year in the River Thames, we know they were widely used throughout London. Hopefully, further research will reveal more about these mysterious lead tokens.

Mudlarking on the Thames Foreshore requires a permit. Learn about rules for mudlarking in London ›

Learn more about mudlarking

Learn more about the experiences of mudlarks, who search the shores of rivers, bays, and seas for historical finds and other objects. Articles ›

This article appeared in the Beachcombing Magazine March/April 2023 issue.