Mother of Pearl Gold Rush

By Mary Meinking

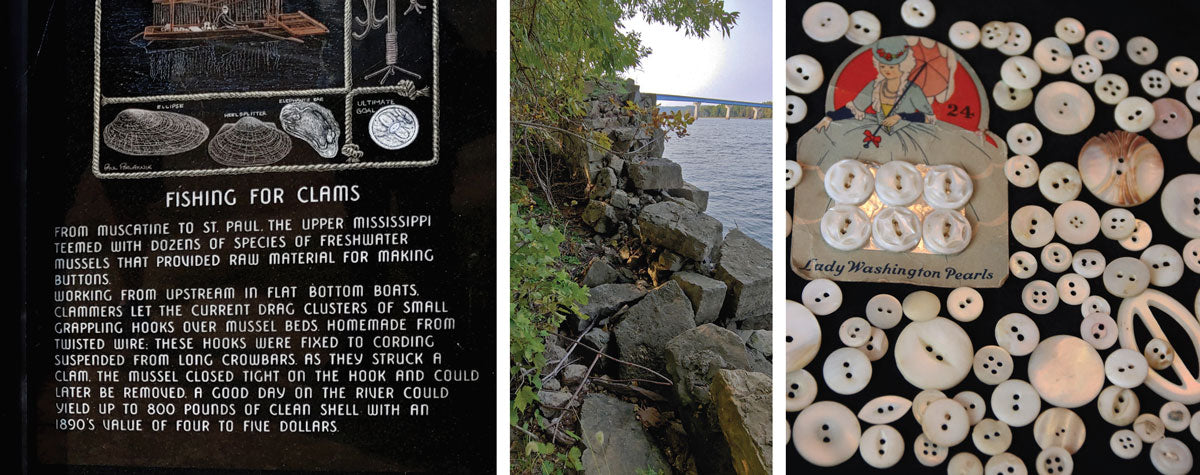

Mother of pearl buttons (Mary Meinking).

Spent shells found on the beach, Scott combing the beach (Mary Meinking).

Creepy skeleton-like eyes stared at us as we walked the shores of the Mississippi River. Was it just an early Halloween prank some kids were playing on us? What was watching our every move?

Informational sign and stone ruins, Lady Washington Pearls card and buttons (Mary Meinking).

Upon closer inspection, we learned the riverbank was littered with hundreds of holey clam shells. Perfect circles of all sizes were cut out of the shells. My husband Scott and I have combed beaches on our travels around the world, but we had never seen anything like this. How and why did the shells get that way? Little did we know that the discarded shells along the riverbank at Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin, and at other communities along the upper Mississippi River, held a rich history.

Curious, we continued exploring the riverbank and wandered through some nearby stone building ruins. Above the riverbank, we found some informational signage about “Fishing for Clams” and “Pearl Buttons.” We guessed that that’s what those shells we found must have been used for…to make buttons!

In the mid-1800s, most people’s clothing was held together with pins or buttons made of wood, bone, or horn. It was a status symbol to have ocean mother of pearl buttons on one’s clothing. Eventually, people found that freshwater mussel shells made beautiful buttons too.

Above: Boepple Button Company and button factory workers (National Pearl Button Museum – Muscatine, IA).

The freshwater mother of pearl button industry on the Mississippi River began in 1891 by German immigrant and button maker John F. Boepple. He found dozens of types of mussels, all with an iridescent sheen, readily available in the Mississippi River. The most sought-after shells for button making were from three-ridge mussels, washboard mussels, and muckets, because they were bigger and flatter. Soon, everyone up and down the river wanted to make their fortune in the button Gold Rush of the Midwest. Half of the river-side population from St. Paul, Minnesota, to Muscatine, Iowa, made their living in the button industry. During the summers, tent cities popped up all along the river so that entire families could help gather shells.

Button-making process from shell to button (National Pearl Button Museum – Muscatine, IA).

Clam fishermen would drag a series of lines with small grappling hooks along the bottom of the river. The open clam would snap shut on the line and be hauled aboard. The fisherman would steam the meat out of the clams as they looked for valuable hidden pearls. They would then sell the shells to button makers. Small one-man shops to large button factories sprang up near the river. Their job was to cut button-sized circles out of the shells, known as “blanks.” The flat discs were polished, and pattern designs were carved into them. Women then drilled two or four holes into each blank to create the buttons. Young girls sorted them into bins separated by sizes and colors. The buttons were then sewn onto cards to be sold around the world.

Freshwater shells and buttons from the collection of Alan Rammer (Kirsti Scott).

In 1905, just down the river in Muscatine, Iowa, workers produced 1.5 billion pearl buttons. That was 37% of the world’s buttons made that year. Soon, Muscatine became known as the Pearl Button Capital of the World. Today, the National Pearl Button Museum in Muscatine is dedicated to the history of freshwater pearl buttons. The museum has interesting displays showing clam fishing and the button-making process, hands-on activities for children, historic videos, and so much more. It is worth a visit if you are ever in the area.

The era of freshwater pearl buttons lasted until the 1940s. By then, the river was so over-clammed that there were no longer many good button-making shells to be found. The fashions had changed, and soon plastic buttons took over the button industry, as they were easier and cheaper to make.

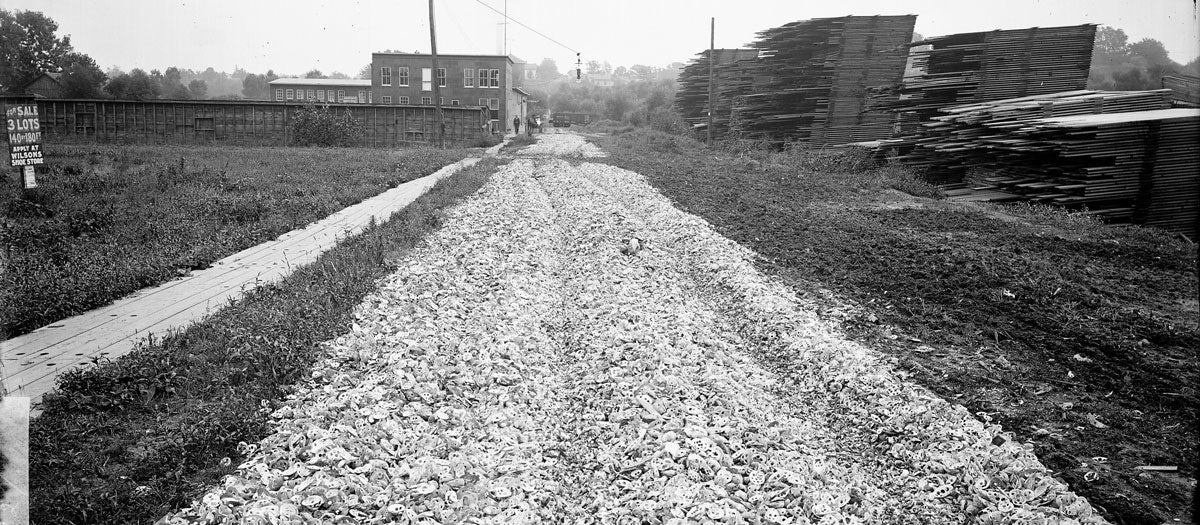

Spent shell-covered road (National Pearl Button Museum – Muscatine, IA).

Over the years, the mountains of button factory shell remains were pulverized to make poultry grit, dumped along the riverbanks, or were crushed to make road beds. Punched shell remnants can still be found by curious beachcombers, like us, who stumble upon them centuries later. The eerie mystery of the staring shells has been solved!

This article appeared in Beachcombing Volume 36: May/June 2023.